Tempo track

11, 13, 16 and .

English translation of the author’s Interlingua original,

Pista de tempo.

A constant tempo isn’t always right

Some music sounds right if played in a fixed cadence. March music is an example. Other types of music don’t sound OK that way, but require tempo rubato, small variations in tempo. The differences may even be large, which may go as far as making it beatless music. Concretely in my small oeuvre, tempo rubato is necessary in Noite sem ti and Seja como for. I wrote about it before, then in Interlingua.

Fine musicians, and the composer

Good musicians, who get the feel of the composition, can spontaneously play in the correct tempo including its variations, even if the indications in the sheet music, like fermatas (symbols 𝄐 e 𝄑), and musical expressions such as ritenuto, rallentando, ritardando, poco a poco più mosso, accelerando, a tempo, are scarce.

But there are many different ways of playing with tempo rubato. How can we know whether musicians’ interpretations are in line with what the composer intended?

In the case of recent music, recordings may exist of the composer playing his own music. Or of an orchestra playing it, conducted by the composer, like in this 1977 example by Míkis Theodorákis (Μίκης Θεοδωράκης) – this time not with singer María Farantúri (Μαρία Φαραντούρη), but with Sofía Mixailídu (Σοφία Μιχαηλίδου) and Margaríta Zorbalá (Μαργαρίτα Ζορμπαλά).

Before the era of video and audio recordings, there were already player pianos, e.g. the pianola, a mechanical piano for which old rolls still exist. Scott Joplin is an example.

Of composers/musician of olden times, like Chopin, we do not know with certainty what were their preferred interpretations.

The old way

Using Copyist Apprentice

In 1994, still using the program Dr T’s Copyist Apprentice, at the start of my piece Seja como for, I indicated the intended small deviations of the strict tempo, directly in the music score. I didn’t put a 𝄐 symbol over a note with a fermata, but I prolonged it, by adding a note with the duration of a quarter or an eighth of the original note, connected to it with a tie.

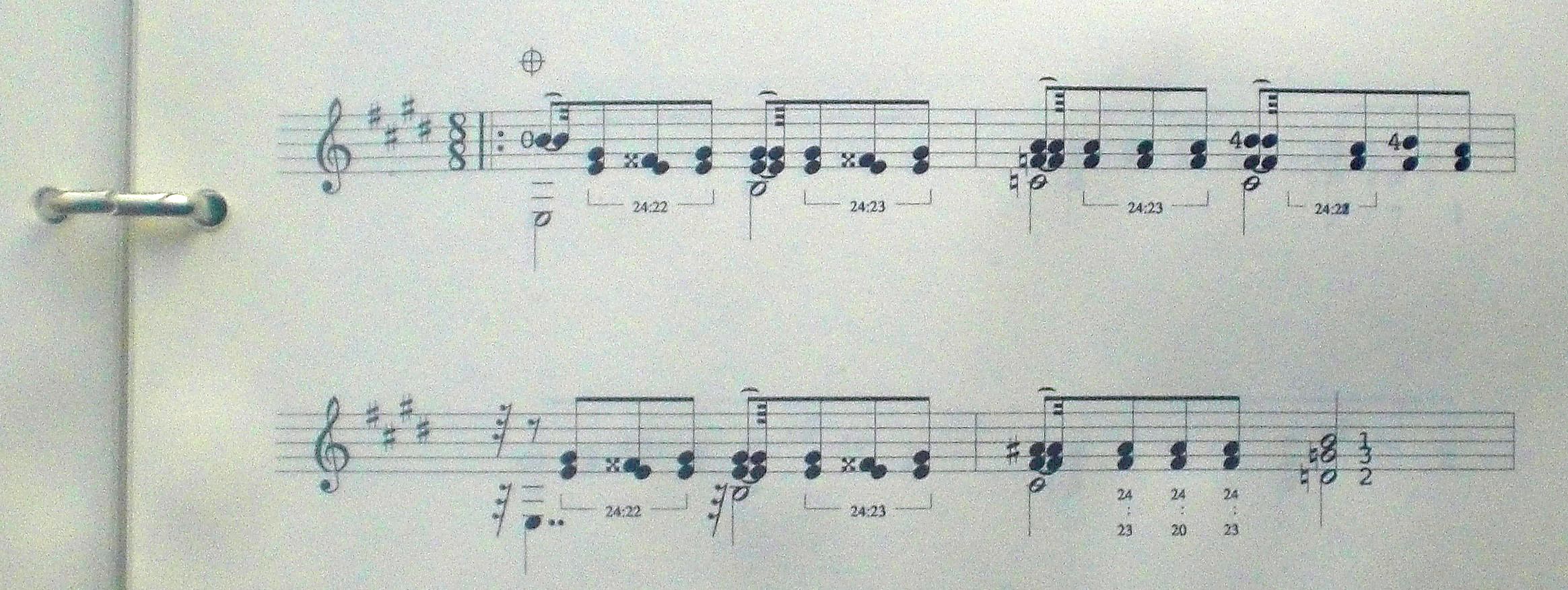

Here is a photo:  , click to enlarge.

Of course, to compensate for the extra length of the note, other notes in

the same measure had to become shorter. This I achieved with something

similar to triplets and quintuplets, but in a more complicated way.

, click to enlarge.

Of course, to compensate for the extra length of the note, other notes in

the same measure had to become shorter. This I achieved with something

similar to triplets and quintuplets, but in a more complicated way.

(About terminology for triplets, quintuplets and sextuplets etc. in Interlingua, see this other article I wrote, and see the discussion in Facebook.)

Using my program guittabl

The basis of the score with temporal adaptations was in experiments with my

tablature file format (I only have an

old program for MSDOS to play

such files):

sejcfor,

from which I quote:

#------------------------------------- # . e b g d A E #------------------------------------- 30/12 0 0 22/12 1 2 22/12 0 2 22/12 1 2 27/12 1 2 23/12 1 2 23/12 0 2 23/12 1 2 #------------------------------------- 27/12 2 3 3 23/12 2 3 23/12 2 3 23/12 2 3 27/12 4 3 3 21/12 2 3 24/12 4 3 24/12 2 3 #-------------------------------------

My program guittabl, and the corresponding tablature format,

assume durations specified in sixteenth notes (semiquavers),

such that a ‘2’ indicates an eighth note or

quaver. But you can also use fractions.

So 24/12 is also a quaver, 27/12 is a quaver with a sixty-fourth note

– a hemidemisemiquaver, which is 3/12 – added to it, and

30/12 is equal to 24/12 plus 6/12, a quaver and half a semiquaver in

combination.

The compensation was done by distributing the additions among the remaining notes, subtracting the partial numerators from 24.

Using Lilypond, the old way

I reconstructed

a fragment of the old score made in Dr T’s Copyist Apprentice,

now in the modern program Lilypond. In Lilypond, a triplet is made thus:

tuplet 3/2 {a b c}, three notes sounding in the normal duration

of two notes. Similarly, a quintuplet is coded as

tuplet 5/4 {a b c d e}, five notes in the time of four. By

analogy I coded the examples in the piece under consideration as

b'8-0_~32 \tuplet 24/22 {<gis e>8 <fisis e> <gis e>}

etc.

The PDF shows the number 24, but unfortunately other details, numbers like 22, 23, 20 which are also essential for the effect, aren’t visible in this modern score. Yet the Midi sounds fine.

Useful?

Obviously this method of specifying tempo rubato isn’t practical, because even musicians who are skilled in playing a prime vista will have great difficulty with this detailed style of notation. It’s better to create an audible representation, like Midi, and let them identify and learn the intended interpretation by listening.

A brilliant idea

I know that self-praise stinks, but on 10 October 2025 I did have a brilliant idea. Or perhaps it was trivial, ordinary and unremarkable. Anyway, my idea was to add an extra track in Lilypond, that does not contain any visible or audible notes, but only tempo indications, almost all of which won’t appear in the sheet music. Taken to the extreme, every note could have its own tempo. Those tempo indications stipulate the details of the intended tempo rubato, without causing a cluttered score.

In Lilypond we can specify notes, according to the conventions in various languages and various countries. And there are rests, indicated by the letter ‘r’.

In the tempo track however, I only use ‘s’ symbols, for

spacer rests. An ‘s’ has a duration, but nothing

appears and nothing is sounded. In addition, following

this instruction, I use:

\set Score.tempoHideNote = ##t

where “##t” means ‘true’, so the tempo indications in the file (see

here and

here) are hidden and

won’t be visible in the score, except for some at the start of a section.

This manner of coding leaves the score unchanged and does not introduce

complications, but the tempo indications do have their effect on the Midi

that is generated.

For debugging purposes the tempo indication can be made to reappear temporarily, to verify whether they are over the correct notes.

The indications of the variable tempo go from the Lilypond file (*.ly)

into the Midi file, so while that is played, intensive calculations will be

necessary to implement the many timing changes. But with today’s hardware,

that won’t present any problems.

Results: ‘Seja como for’ with a fixed beat, and as intended by the composer, and ‘Noite sem ti’ with a fixed beat, and as intended.

Videos?

In August 2024 I wrote: “[...] optimum conditions, that would also be applicable to musical videos that I intend to produce one day.” This was to clarify my intentions as a composer.

However since mid August 2025 I have a medical problem in my right hand – the cause is still unknown and investigations are ongoing. As a result I can hardly still play the guitar. Perhaps some day it will be possible again, nobody knows.

Clearly this added much to my satisfaction about that idea I had on 10 October 2025!

Tascam

I must still have some old cassettes with recordings then made of some

of my pieces. But there is a mechanical problem, the Tascam Portastudio

(that includes a dbx system for dynamic compression and

noise reduction) won’t turn. Perhaps in future I might manage to repair

it, play the old cassettes, and digitise and publish them, in addition

to the tempo tracks and Midi.

See also the swing script of Lilypond.

Copyright © 2026 by R. Harmsen.